How do you turn a rubbish dump into an uplifting new home? Ian Tucker travels to Peckham to meet the man who found the answer in the sky

'A lot of life is about luck, but if you sit around watching TV, you won't be lucky. Luck is about how much you engage with the world, with people, and how much you inspire people to do something special.' It's slightly cornball self-help-book blather, but from the mouth of Monty Ravenscroft, spoken as he waves you round his family's snazzy new home, built on a driveway of land in south London, it begins to take on the feel of profound wisdom.

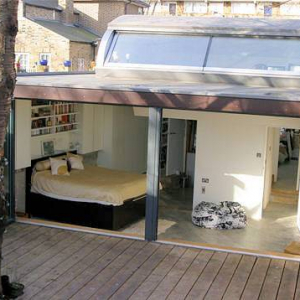

The house is wedged between two Georgian villas in a conservation area in Peckham. From the street it doesn't look much bigger than a Portakabin, but once inside you're amazed at the space and brightness it contains. Much of this is down to the house's unique sliding roof. Working much like a car sunroof, the ceiling to the main living area is a large expanse of glass that retracts at the press of a button to reveal the sky and airplanes passing overhead (and slides back at the first sign of rain, thanks to a sensor).

As Monty's partner Claire Loewe says, 'The skylight is wonderful; it changes the atmosphere of the room. There's something about opening up the ceiling that grounds you.'

Without the roof the house couldn't exist: the structure butts up so closely to the neighbouring houses that side windows were impractical. As Monty points out, when he found the plot there was no obvious way to build a conventional house. Which, in fact, was exactly what he was looking for: 'If we could find a plot that couldn't have windows, then it was a site we could probably afford,' he explains.

Monty learnt the sunroof trick when he found himself making retracting roofs for the architect Richard Paxton. He is what you might call an 'outsider engineer', who spent his teenage years building custom cars and even a rotating summer house on his parent's farm. Later, he became a regular on television's Scrapheap Challenge.

Armed with this knowledge he set about finding a London plot and, after some five years of searching, he went to an auction and paid £40,000 for a 'bit of shitty land with rubbish on it' with no firm promise of planning permission.

Two-and-a-half years of persuading planning officers later, the concrete foundations were laid - but only after his dad had remortgaged his own house to pay for the construction because no bank would lend them the money.

Grand Designs came along to film the entertainment as Monty persuaded architects to work for love not money, encouraged friends to discover their hod-carrying talents, built models out of cereal packets and managed to erect the house's steel framework without the help of costly crane - his budget to finish the house was £130,000.

Monty's particular ideas and vision are found all over the house. It is full of unusual touches. A bathroom sink concealed in a drawer. An open-plan ensuite shower. A translucent glass toilet wall that adjoins the lounge: 'When it's backlit you get silhouettes - which is more of a problem for men than women.'

Possibly the quirkiest feature can be found in the bedroom, where you'll find a bed that can be slid sideways to reveal a bath. 'I don't have time for baths,' Monty explains. 'Most houses have baths because it's what you're supposed to have - they take up lots of space but are never used. People have showers in baths, which is fine but tedious. With this bath, bathing is a special occasion, a theatrical thing.'

Monty is proud of all these details. How every wall 'floats' without touching ceiling, floor or another wall. The hidden stair rail fixings. The space-saving pigeon steps to the two mezzanine bedrooms that not only float but also gently spring as you ascend them - 'People find them more disconcerting than I thought.'

Wilder ideas (an open-plan toilet in the lounge as a monument to thinking) were moderated by his wife's Claire's taste. 'I grew up in a farmhouse and Claire grew up in a fashion house,' he jokes.

Claire runs her tango-teaching business from the studio at the front of the house, dancing on sycamore floorboards made from a tree felled to make way for the build. 'The studio is a dream come true. It has radically changed my life. I can babysit and still be at work.' When they moved in, their son Flint was a month old. 'I wonder if when he gets older and visits friends' houses, he'll look under the bed for the bath,' says Claire.

Living with a small child in such a unique house brings complications. 'We need a stairgate for Flint, but we can't get one off the shelf - everything is bespoke, it can take forever.'

And although for the purposes of Grand Designs the house was finished more than a year ago, Monty is constantly finishing and adding new features. On the day of The Observer's visit a mural was being painted on the dance studio's ceiling, and three other workmen were busy with lathes, spotlights and landscaping.

Needless to say, the build has gone over budget. Monty reckons they've now spent around £210,000, but the banks will lend him money now and his father's house is safe. Financial control comes in the form of a rodent: 'We have a little mouse,' says Clare, 'who always crawls out when we're sitting here poring over our statements, talking about money. I think the mouse will go when our finances are more sorted.'

The building is a monument to Monty and Claire's innovation and determination. 'There were lots of battles to get this where it is. A lot of people have helped make it happen. In some ways it's not worth it - all I get at the end is a house. Whereas if I can help stop unblock the log jam of regulations and encourage others, then great,' says Monty. With this in mind, they are welcoming people into their home as part of the Open House weekend.

Ultimately, Monty has no doubts it was worth the struggle. 'We ended up with such a amazing place to live in. We come back to it and think it's still here, we're still allowed to live in it. We lie in bed and think "We did this."'